Again the Devil Deceived a Third of the Angels of Heaven

In Abrahamic religions, fallen angels are angels who were expelled from sky. The literal term "fallen affections" appears neither in the Bible nor in other Abrahamic scriptures, just is used to depict angels cast out of heaven[1] or angels who sinned. Such angels often tempt humans to sin.

The idea of fallen angels derived from the Book of Enoch, a Jewish pseudepigraph, or the assumption that the "sons of God" (בני האלוהים) mentioned in Genesis 6:ane–4 are angels. In the period immediately preceding the composition of the New Testament, some sects of Judaism, also every bit many Christian Church Fathers, identified these same "sons of God" as fallen angels. During the late Second Temple period the biblical giants were sometimes considered the monstrous offspring of fallen angels and homo women. In such accounts, God sends the Great Deluge to purge the earth of these creatures; their bodies are destroyed, yet their peculiar souls survive, henceforth roaming the earth as demons. Rabbinic Judaism and Christian government after the tertiary century rejected the Enochian writings and the notion of an illicit union betwixt angels and women producing giants. Christian theology indicates the sins of fallen angels occur before the showtime of human history. Appropriately, fallen angels became identified with those led past Satan in rebellion against God, also equated with demons.

Evidence for the belief in fallen angels amid Muslims tin can be traced back to reports attributed to some of the companions of Muhammad, such as Ibn Abbas (619–687) and Abdullah ibn Masud (594–653).[2] At the same time, some Islamic scholars opposed the assumption of fallen angels past stressing the piety of angels supported past verses of Quran, such as 16:49 and 66:vi, although none of these verses declare angels as immune from sin.[three] One of the first opponents of fallen angels was the early and influential Islamic ascetic Hasan of Basra (642–728). To back up the doctrine of infallible angels, he pointed at verses which stressed the piety of angels, while simultaneously reinterpreting verses which might imply acknowledgement of fallen angels. For that reason, he read the term mala'ikah (angels) in reference to Harut and Marut, two possible fallen angels mentioned in 2:102, as malikayn (kings) instead of malā'ikah (angels), depicting them as ordinary men and advocated the belief that Iblis was a jinn and had never been an angel before.[4] The precise degree of celestial fallibility is not clear even amidst scholars who accepted fallen angels; according to a common assertion, impeccability applies just to the messengers among angels or as long every bit they remain angels.[5]

Academic scholars accept discussed whether or not the Quranic jinn are identical to the biblical fallen angels. Although the different types of spirits in the Quran are sometimes hard to distinguish, the jinn in Islamic traditions seem to differ in their major characteristics from fallen angels.[1] [a]

2d Temple period [edit]

The concept of fallen angels derives mostly from works dated to the Second Temple catamenia betwixt 530 BC and 70 AD: in the Book of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees and the Qumran Book of Giants; and perhaps in Genesis half dozen:1–four.[7] A reference to heavenly beings called "Watchers" originates in Daniel 4, in which there are 3 mentions, twice in the atypical (v. 13, 23), one time in the plural (v. 17), of "watchers, holy ones". The Ancient Greek word for watchers is ἐγρήγοροι ( egrḗgoroi , plural of egrḗgoros ), literally translated as "wakeful".[8] Some scholars consider it almost likely that the Jewish tradition of fallen angels predates, fifty-fifty in written grade, the limerick of Gen 6:1–4.[9] [x] [b] In the Volume of Enoch, these Watchers "cruel" later they became "enamored" with human women. The Second Volume of Enoch (Slavonic Enoch) refers to the same beings of the (Starting time) Volume of Enoch, now chosen Grigori in the Greek transcription.[12] Compared to the other Books of Enoch, fallen angels play a less significant part in 3 Enoch. 3 Enoch mentions only three fallen angels called Azazel, Azza and Uzza. Similar to The starting time Book of Enoch, they taught sorcery on earth, causing corruption.[13] Unlike the first Volume of Enoch, there is no mention of the reason for their autumn and, according to 3 Enoch 4.half-dozen, they also subsequently appear in heaven objecting to the presence of Enoch.

ane Enoch [edit]

Chester Beatty XII, Greek manuscript of the Book of Enoch, quaternary century

According to one Enoch vii.2, the Watchers get "enamoured" with human women[14] and have intercourse with them. The offspring of these unions, and the knowledge they were giving, corrupt human beings and the earth (i Enoch 10.eleven–12).[14] Eminent amid these angels are Shemyaza, their leader, and Azazel. Like many other fallen angels mentioned in 1 Enoch 8.1–9, Azazel introduces men to "forbidden arts", and it is Azazel who is rebuked by Enoch himself for illicit pedagogy, as stated in 1 Enoch 13.1.[15] According to 1 Enoch 10.half dozen, God sends the archangel Raphael to concatenation Azazel in the desert Dudael as punishment. Farther, Azazel is blamed for the corruption of earth:

i Enoch ten:12: "All the globe has been corrupted by the furnishings of the teaching of Azazyel. To him therefore accredit the whole law-breaking."

An etiological interpretation of 1 Enoch deals with the origin of evil. By shifting the origin of mankind's sin and their misdeeds to illicit angel educational activity, evil is attributed to something supernatural from without. This motif, in 1 Enoch, differs from that of later on Jewish and Christian theology; in the latter evil is something from within.[16] According to a paradigmatic interpretation, ane Enoch might bargain with illicit marriages between priests and women. As evident from Leviticus 21:i–15, priests were prohibited to ally impure women. Accordingly, the fallen angels in 1 Enoch are the priests counterpart, who defile themselves by marriage. Just like the angels are expelled from heaven, the priests are excluded from their service at the altar. Unlike about other apocalyptic writings, ane Enoch reflects a growing dissatisfaction with the priestly establishments in Jerusalem in 3rd century BC. The paradigmatic interpretation parallels the Adamic myth in regard of the origin of evil: In both cases, transcending ones own limitations inherent in their ain nature, causes their fall. This contrasts the etiological interpretation, which implies another power as well God, in heaven. The latter solution therefore poorly fits into monotheistic idea.[17] Otherwise, the introduction to illicit knowledge might reflect a rejection of foreign Hellenistic culture. Accordingly, the fallen angels correspond creatures of Greek mythology, which introduced forbidden arts, used past Hellenistic kings and generals, resulting in oppression of Jews.[xviii]

two Enoch [edit]

The concept of fallen angels is likewise in the 2nd Volume of Enoch. It tells about Enoch'due south rise through the layers of heaven. During his journeying, he encounters fallen angels imprisoned in the 2nd sky. At first, he decides to pray for them, but refuses to practice so, since he himself every bit merely human, would not be worthy to pray for angels. In the 5th sky however, he meets other rebellious angels, here called Grigori, remaining in grief, not joining the heavenly hosts in vocal. Enoch tries to cheer them upward by telling about his prayers for their beau angels and thereupon they join the heavenly liturgy.[19]

Strikingly, the text refers to the leader of the Grigori equally Satanail and not equally Azael or Shemyaza, as in the other Books of Enoch.[20] But the Grigori are identified with the Watchers of 1 Enoch.[21] [22]

The narration of the Grigori in two Enoch 18:1–seven, who went down on to globe, married women and "befouled the earth with their deeds", resulting in their confinement under the world, shows that the author of 2 Enoch knew about the stories in 1 Enoch.[20] The longer recension of ii Enoch, affiliate 29 refers to angels who were "thrown out from the meridian" when their leader tried to become equal in rank with the Lord'southward power (2 Enoch 29:1–4), an idea probably taken from Ancient Canaanite organized religion nigh Attar, trying to rule the throne of Baal. The equation of an angel called Satanail with a deity trying to usurp the throne of a college deity, was also adapted by later Christian in regard to the autumn of Satan.[23]

Jubilees [edit]

The Book of Jubilees, an ancient Jewish religious work, accepted as approved by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Beta Israel, refers to the Watchers, who are among the angels created on the first day.[24] [25] Withal, unlike the (commencement) Book of Enoch, the Watchers are commanded by God to descend to earth and to instruct humanity.[26] [27] It is only later they copulate with human women that they transgress the laws of God.[28] These illicit unions result in demonic offspring, who boxing each other until they die, while the Watchers are bound in the depths of the earth as punishment.[29] In Jubilees 10:i, another angel called Mastema appears every bit the leader of the evils spirits.[28] He asks God to spare some of the demons, so he might use their aid to lead humankind into sin. Later, he becomes their leader:[28]

"'Lord, Creator, let some of them remain before me, and permit them harken to my vox, and do all that I shall say unto them; for if some of them are not left to me, I shall not be able to execute the ability of my will on the sons of men; for these are for corruption and leading off-target earlier my judgment, for great is the wickedness of the sons of men.' (x:8)

Both the (get-go) Volume of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees include the motif of angels introducing evil to humans. However, unlike the Book of Enoch, the Volume of Jubilees does not hold that evil was caused by the fall of angels in the first place, although their introduction to sin is affirmed. Farther, while the fallen angels in the Volume of Enoch are interim against God'due south will, the fallen angels and demons in the Book of Jubilees seem to have no power independent from God simply simply human activity within his ability.[thirty]

Rabbinic Judaism [edit]

Although the concept of fallen angels developed from Judaism during the Second Temple menses, rabbis from the second century onward turned against the Enochian writings, probably in gild to prevent young man Jews from worship and veneration of angels. Thus, while many angels were individualized and sometimes venerated during the 2nd Temple period, the status of angels was degraded to a class of creatures on the same level of humans, thereby emphasizing the attendance of God. The second-century rabbi Shimon bar Yochai cursed everyone who explained the term sons of God as angels. He stated sons of God were actually sons of judges or sons of nobles. Evil was no longer attributed to heavenly forces, at present it was dealt as an "evil inclination" (yetzer hara) inside humans.[31] Nonetheless, narrations of fallen angels do appear in later rabbinic writings. In some Midrashic works, the "evil inclination" is attributed to Samael, who is in charge of several satans in order to test humanity.[32] [33] Nevertheless, these angels are still subordinate to God; the reacceptance of insubordinate angels in Midrashic soapbox was posterior and probably influenced by the role of fallen angels in Islamic and Christian lore.[34]

The idea of rebel angels in Judaism appears in the Aggadic-Midrashic work Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, which shows not one, but two falls of angels. The showtime 1 is attributed to Samael, who refuses to worship Adam and objects to God favoring Adam over the angels, ultimately descending onto Adam and Eve to tempt them into sin. This seems rooted in the motif of the autumn of Iblis in the Quran and the fall of Satan in the Cavern of Treasures.[35] The second fall echoes the Enochian narratives. Again, the "sons of God" mentioned in Gen vi:one–4 are depicted as angels. During their fall, their "force and stature became like the sons of homo" and once more, they give beingness to the giants by intercourse with human being women.[35]

Kabbalah [edit]

Although not strictly speaking fallen, evil angels reappear in Kabbalah. Some of them are named after angels taken from the Enochian writings, such as Samael.[36] According to the Zohar, but as angels can be created by virtue, evil angels are an incarnation of human vices, which derive from the Qliphoth, the representation of impure forces.[37]

However, the Zohar besides recalls a narration of ii angels in a fallen state, chosen Aza and Azael. These angels are cast down from the heaven afterward mistrusting Adam for his inclination towards sin.[38] Once on Globe, they complete the Enochian narrative by teaching magic to humans and producing offspring with them, too as consorting with Lilith (hailed as "the sinner"). In the narrative, the Zohar affirms just simultaneously prohibits magical practices.[39] As a punishment, God puts the angels in chains, but they notwithstanding copulate with the demoness Naamah, who gives birth to demons, evil spirits and witches.[38]

Christianity [edit]

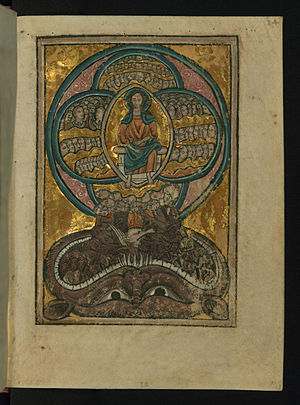

God sits on a throne inside a mandorla. The rebelling angels are depicted every bit falling out of heaven and into a hell, in the shape of a oral cavity. As they fall, the angels become demons.

Bible [edit]

Luke ten:18 refers to "Satan falling from heaven" and Matthew 25:41 mentions "the Devil and his angels", who volition be thrown into hell. All Synoptic Gospels place Satan as the leader of demons.[forty] Paul the Apostle (c. 5 – c. 64 or 67) states in 1 Corinthians 6:3 that there are angels who volition be judged, implying the existence of wicked angels.[40] 2 Peter 2:four and Jude 1:6 refer paraenetically to angels who have sinned confronting God and await punishment on Judgement Twenty-four hours.[41] The Book of Revelation, chapter 12, speaks of Satan equally a nifty red dragon whose "tail swept a tertiary function of the stars of heaven and cast them to the earth".[42] In verses 7–9, Satan is defeated in the War in Heaven against Michael and his angels: "the great dragon was thrown down, that aboriginal ophidian who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the globe and his angels were thrown downward with him".[43] Nowhere within the New Testament writings are fallen angels identified with demons,[40] but by combining the references to Satan, demons and angels, early Christian exegetes equated fallen angels with demons, for which Satan was regarded as the leader.[40] [44]

Origen and other Christian writers linked the fallen morning star of Isaiah xiv:12 of the Onetime Testament to Jesus' statement in Luke 10:18 that he "saw Satan autumn similar lightning from heaven", as well as a passage about the autumn of Satan in Revelation 12:viii–nine.[45] The Latin word lucifer, equally introduced in the late fourth-century AD Vulgate, gave rise to the name for a fallen angel.[46]

Christian tradition has associated Satan not only with the image of the morning time star in Isaiah xiv:12, but also with the denouncing in Ezekiel 28:eleven–19 of the rex of Tyre, who is spoken of equally having been a "cherub". The Church Fathers saw these 2 passages every bit in some ways parallel, an estimation also testified in apocryphal and pseudepigraphic works.[47] Notwithstanding, "no modern evangelical commentary on Isaiah or Ezekiel sees Isaiah 14 or Ezekiel 28 as providing information about the fall of Satan".[48]

Early Christianity [edit]

During the menstruum immediately before the ascent of Christianity, the intercourse betwixt the Watchers and homo women was often seen as the beginning fall of the angels.[49] Christianity stuck to the Enochian writings at least until the tertiary century.[50] Many Church Fathers such as Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria and Lactantius[51] [52] accepted the association of the angelic descent myth to the sons of God passage in Genesis 6:1–iv.[51] Withal, some ascetics, such as Origen (c. 184 – c. 253),[53] rejected this interpretation. According to the Church Fathers who rejected the doctrine by Origen, these angels were guilty of having transgressed the limits of their nature and of desiring to leave their heavenly abode to feel sensual experiences.[54] Irenaeus referred to fallen angels as apostates, who volition be punished past an everlasting fire. Justin Martyr (c. 100 – c. 165) identified pagan deities every bit fallen angels or their demonic offspring in disguise. Justin also held them responsible for Christian persecution during the offset centuries.[55] Tertullian and Origen also referred to fallen angels as teachers of star divination.[56]

The Babylonian male monarch, who is described equally a fallen "forenoon star" in Isaiah 14:1–17, was probably the starting time time identified with a fallen angel past Origen.[57] [58] This description was interpreted typologically both every bit an angel and a human king. The prototype of the fallen morning time star or angel was thereby applied to Satan by early on Christian writers,[59] [sixty] following the equation of Lucifer to Satan in the pre-Christian century.[61]

Catholicism [edit]

Fallen angels dwelling in Hell

Innichen (Due south Tyrol), Saint Michael Parish Church: Frescos depicting the autumn of the rebelling angels past Christoph Anton Mayr (1760)

Past the third century, Christians began to decline the Enochian literature. The sons of God came to be identified merely with righteous men, more precisely with descendants of Seth who had been seduced by women descended from Cain. The cause of evil was shifted from the superior powers of angels, to humans themselves, and to the very first of history; the expulsion of Satan and his angels on the one hand and the original sin of humans on the other mitt.[50] [62] Nonetheless, the Book of Watchers, which identified the sons of God with fallen angels, was not rejected by Syriac Christians.[63] Augustine of Hippo'south work Civitas Dei (5th century) became the major opinion of Western demonology and for the Cosmic Church.[64] He rejected the Enochian writings and stated that the sole origin of fallen angels was the rebellion of Satan.[65] [66] Equally a result, fallen angels came to be equated with demons and depicted as not-sexual spiritual entities.[67] The exact nature of their spiritual bodies became another topic of dispute during the Middle Ages.[64] Augustine based his descriptions of demons on his perception of the Greek Daimon.[64] The Daimon was thought to be a spiritual being, composed of ethereal matter, a notion also used for fallen angels by Augustine.[68] However, these angels received their ethereal body only after their autumn.[68] Later scholars tried to explicate the details of their spiritual nature, asserting that the ethereal body is a mixture of fire and air, but that they are all the same composed of material elements. Others denied whatever physical relation to material elements, depicting the fallen angels equally purely spiritual entities.[69] Only even those who believed the fallen angels had ethereal bodies did non believe that they could produce any offspring.[70] [71]

Augustine, in his Civitas Dei describes two cities (Civitates) distinct from each other and opposed to each other like light and darkness.[72] The earthly city is caused by the act of rebellion of the fallen angels and is inhabited by wicked men and demons (fallen angels) led by Satan. On the other paw, the heavenly city is inhabited by righteous men and the angels led by God.[72] Although, his ontological division into ii different kingdoms shows resemblance of Manichean dualism, Augustine differs in regard of the origin and power of evil. In Augustine works, evil originates from complimentary volition. Augustine always emphasized the sovereignty of God over the fallen angels.[73] Accordingly, the inhabitants of the earthly metropolis can only operate inside their God-given framework.[66] The rebellion of angels is also a result of the God-given freedom of option. The obedient angels are endowed with grace, giving them a deeper understanding of God'south nature and the order of the cosmos. Illuminated by God-given grace, they became incapable of feeling whatever desire for sin. The other angels, even so, are not blessed with grace, thus they remain capable of sin. After these angels decide to sin, they fall from heaven and go demons.[74] In Augustine's view of angels, they cannot exist guilty of carnal desires since they lack flesh, but they tin can be guilty of sins that are rooted in spirit and intellect such every bit pride and envy.[75] However, after they have made their decision to rebel against God, they cannot turn back.[76] [77] The Catechism of the Catholic Church does non accept "the autumn of the angels" literally, but as a radical and irrevocable rejection of God and his reign by some angels who, though created as skilful beings, freely chose evil, their sin being unforgivable because of the irrevocable grapheme of their selection, not because of any defect in infinite divine mercy.[78] Present-mean solar day Catholicism rejects Apocatastasis, the reconciliation with God suggested by the Church Male parent Origen.[79]

Orthodox Christianity [edit]

Eastern Orthodox Christianity [edit]

Similar Catholicism, Eastern Orthodox Christianity shares the bones belief in fallen angels as spiritual beings who rebel against God. Different Catholicism, however, there is no established doctrine about the exact nature of fallen angels, only Eastern Orthodox Christianity unanimously agrees that the power of fallen angels is always junior to God. Therefore, belief in fallen angels can e'er be assimilated with local lore, as long information technology does not interruption basic principles and is in line with the Bible.[80] Historically, some theologians even tend to propose that fallen angels could be rehabilitated in the world to come up.[81] Fallen angels, merely like angels, play a significant role in the spiritual life of believers. Every bit in Catholicism, fallen angels tempt and incite people into sin, merely mental affliction is too linked to fallen angels.[82] Those who have reached an advanced degree of spirituality are fifty-fifty thought to be able to envision them.[82] Rituals and sacraments performed past Eastern Orthodoxy are thought to weaken such demonic influences.[83]

Ethiopian Church building [edit]

Unlike well-nigh other Churches, the Ethiopian Church accepts one Enoch and the Volume of Jubilees equally canonical.[84] As a effect, the Church building believes that human sin does not originate in Adam's transgression solitary, but as well from Satan and other fallen angels. Together with demons, they continue to crusade sin and corruption on world.[85]

Protestantism [edit]

Similar Catholicism, Protestantism continues with the concept of fallen angels as spiritual entities unrelated to flesh,[67] simply information technology rejects the angelology established by Catholicism. Martin Luther's (1483–1546) sermons of the angels merely recount the exploits of the fallen angels, and does not deal with an angelic bureaucracy.[86] Satan and his fallen angels are responsible for some misfortune in the globe, only Luther always believed that the power of the good angels exceeds those of the fallen ones.[87] The Italian Protestant theologian Girolamo Zanchi (1516–1590) offered further explanations for the reason backside the fall of the angels. According to Zanchi, the angels rebelled when the incarnation of Christ was revealed to them in incomplete form.[67] While Mainline Protestants are much less concerned with the crusade of celestial fall, arguing that information technology is neither useful nor necessary to know, other Protestant churches do take fallen angels every bit more of a focus.[67]

Islam [edit]

Depiction of Iblis, blackness-faced and without hair (meridian-correct of the motion-picture show). He refuses to prostrate himself with the other angels.

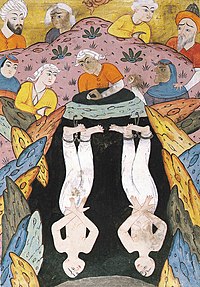

The angels Harut and Marut punished by hanging over the well, without wings and hair.

The concept of fallen angels is debated in Islam.[88] Opposition to the possibility of erring angels tin can be attested as early as Hasan of Basra.[c] On the other hand Abu Hanifa (d. 767), founder of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, distinguished between obedient angels, disobedient angels and unbelievers amongst the angels, who in turn differ from the jinn and devils.[90] Al-Taftazani (1322 Advertising –1390 AD) argued that angels might slip into mistake and are rebuked, similar Harut and Marut, just could not get unbelievers, like Iblis.[91]

The Quran mentions the fall of Iblis in several Surahs. Surah Al-Anbiya states that angels claiming divine honors were to be punished with hell.[92]Further, Surah ii:102 implies that a pair of fallen angels introduces magic to humanity. However, the latter angels did not accompany Iblis. Fallen angels work in entirely unlike ways in the Quran and Tafsir.[93] According to the Isma'ilism work Umm al-Kitab, Azazil boasts about himself being superior to God until he is thrown into lower celestial spheres and ends up on earth.[94] Iblis is often described as beingness chained in the lowest pit of hell (Sijjin) by various scholars, including Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1150–1210)[95] and commands, according to Al-Tha'alibis (961–1038) Qisas Al-Anbiya, his host of rebel angels (shayāṭīn) and the fiercest jinn (ifrit) from there.[96] In a Shia narrative from Ja'far al-Sadiq (700 or 702–765), Idris (Enoch) meets an angel, which the wrath of God falls upon, and his wings and hair are cut off; afterward Idris prays for him to God, his wings and hair are restored. In render they go friends and at his request the angel takes Idris to the heavens to meet the affections of decease.[97] In Shia traditions, a cherub called Futrus was cast out from sky and fell to the earth in the form a ophidian.[98]

Some contempo non-Islamic scholars propose Uzair, who is according to Surah ix:30 called a son of God by Jews, originally referred to a fallen angel.[99] While exegetes almost unanimously identified Uzair equally Ezra,[d] in that location is no historical evidence that the Jews chosen him son of God. Thus, the Quran may refer non to the earthly Ezra, but to the heavenly Ezra, identifying him with the heavenly Enoch, who in turn became identified with the angel Metatron (besides chosen lesser YHWH) in merkabah mysticism.[101]

Iblis [edit]

The Quran repeatedly tells almost the fall of Iblis. According to Quran 2:30,[102] the angels object to God's intention to create a human, because they will cause corruption and shed blood,[103] echoing the business relationship of 1 Enoch and the Book of Jubilees. This happens later the angels notice men causing unrighteousness.[104] However, afterward God demonstrates the superiority of Adam'southward knowledge in comparison to the angels, He orders them to prostrate themselves. Just Iblis refuses to follow the instruction. When God asks for the reason behind Iblis' refusal, he boasts about himself being superior to Adam, because he is fabricated of burn. Thereupon God expels him from heaven. In the early Meccan flow, Iblis appears as a degraded affections.[105] But since he is called a jinni in Surah 18:50, some scholars contend that Iblis is actually non an angel, merely an entity apart, stating he is merely allowed to join the company of angels as a advantage for his previous righteousness. Therefore, they reject the concept of fallen angels and emphasize the dignity of angels by quoting certain Quranic verses similar 66:6 and 16:49, distinguishing between infallible angels and jinn capable of sin. Withal, the notion of jinni cannot clearly exclude Iblis from being an angel.[106] According to Ibn Abbas, angels who guard the jinan (here: heavens) are called Jinni, just as humans who were from Mecca are called Mecci, but they are not related to the jinn-race.[107] [108] Other scholars affirm that a jinn is everything hidden from human eye, both angels and other invisible creatures, thus including Iblis to a group of angels. In Surah xv:36, God grants Iblis' request to prove the unworthiness of humans. Surah 38:82 as well confirms that Iblis' intrigues to pb humans off-target are permitted by God'due south power.[109] Withal, as mentioned in Surah 17:65, Iblis' attempts to mislead God's servants are destined to neglect.[109] The Quranic episode of Iblis parallels another wicked affections in the earlier Books of Jubilees: Similar Iblis, Mastema requests God's permission to tempt humanity, and both are limited in their power, that is, not able to deceive God's servants.[110] However, the motif of Iblis' disobedience derives not from the Watcher mythology, simply can be traced back to the Cave of Treasures, a piece of work that probably holds the standard explanation in Proto-orthodox Christianity for the celestial autumn of Satan.[103] According to this explanation, Satan refuses to prostrate himself before Adam, because he is "fire and spirit" and thereupon Satan is banished from heaven.[111] [103] Unlike the majority opinion in afterwards Christianity, the idea that Iblis tries to usurp the throne of God is alien to Islam and due to its strict monotheism unthinkable.[112]

Harut and Marut [edit]

Harut and Marut are a pair of angels mentioned in Surah two:102 instruction magic. Although the reason behind their stay on earth is not mentioned in the Quran, the post-obit narration became canonized in Islamic tradition.[113] The Quran exegete Tabari attributed this story to Ibn Masud and Ibn Abbas[114] and is also attested by Ahmad ibn Hanbal.[115] Briefly summarized, the angels complain about the mischievousness of mankind and make a request to destroy them. Consequently, God offers a test to determine whether or not the angels would do better than humans for long: the angels are endowed with human-like urges and Satan has power over them. The angels choose two (or in some accounts three) amidst themselves. Notwithstanding, on Earth, these angels entertain and act upon sexual desires and get guilty of idol worship, whereupon they even kill an innocent witness of their actions. For their deeds, they are not allowed to ascend to heaven once more.[116] Probably the names Harut and Marut are of Zoroastrian origin and derived from two Amesha Spentas called Haurvatat and Ameretat.[117] Although the Quran gave these fallen angels Iranian names, mufassirs recognized them as from the Book of Watchers. In accord with iii Enoch, al-Kalbi (737 Advertizing – 819 AD) named 3 angels descending to earth, and he even gave them their Enochian names. He explained that one of them returned to heaven and the other ii changed their names to Harut and Marut.[118] However, like in the story of Iblis, the story of Harut and Marut does non contain any trace of angelic revolt. Rather, the stories about fallen angels are related to a rivalry between humans and angels.[119] Equally the Quran affirms, Harut and Marut are sent by God and, different the Watchers, they only instruct humans to witchcraft past God's permission,[120] just equally Iblis tin can simply tempt humans past God's permission.[121]

Literature [edit]

In the Divine Comedy (1308–1320) by Dante Alighieri, fallen angels guard the City of Dis surrounding the lower circles of hell. They mark a transition: While in previous circles, the sinners are condemned for sins they but could non resist, after on, the circles of hell are filled with sinners who deliberately insubordinate confronting God, such equally fallen angels or Christian heretics.[122]

In John Milton'due south 17th-century ballsy poem Paradise Lost, both obedient and fallen angels play an important part. They appear as rational individuals:[123] their personality is similar to that of humans.[124] The fallen angels are named later entities from both Christian and Pagan mythology, such as Moloch, Chemosh, Dagon, Belial, Beelzebub and Satan himself.[125] Post-obit the approved Christian narrative, Satan convinces other angels to alive costless from the laws of God, thereupon they are cast out of heaven.[124] The epic verse form starts with the fallen angels in hell. The first portrayal of God in the book is given past fallen angels, who describe him as a questionable tyrant and arraign him for their fall.[126] Outcast from sky, the fallen angels establish their ain kingdom in the depths of hell, with a capital chosen Pandæmonium. Unlike most earlier Christian representations of hell, information technology is not the master place for God to torture the sinners, simply the fallen angels' own kingdom. The fallen angels even build a palace, play music and freely fence. Notwithstanding, without divine guidance, the fallen angels themselves turn hell into a place of suffering.[127]

The idea of fallen angels plays a meaning part in the various poems of Alfred de Vigny. In Le Déluge (1823),[128] the son of an affections and a mortal woman learns from the stars about the keen deluge. He seeks refuge with his dear on Mount Ararat, hoping that his celestial father volition save them. But since he does not appear, they are defenseless by the flood. Éloa (1824) is about a female affections created by the tears of Jesus. She hears about a male angel, expelled from heaven, whereupon she seeks to comfort him, but goes to perdition as a outcome.[129]

Run across too [edit]

- Archon

- Fairy

- Nephilim

Notes [edit]

- ^ In classical Islamic traditions, the jinn are often thought of as a race of Pre-Adamites,[6] who dwelt on earth. However, their ethereal body, similar to the Christian notion of fallen angels, would permit them to climb up to sky to obtain cognition, thus passing secret information to soothsayers, a concept corresponding with the Greek Daimon. The Quran also refers to the belief of jinn, trying to climb up to heaven. Equally Patricia Crone points out, one of the characteristics of fallen angels is, that they fall from heaven, not that they try to become back to information technology.[1]

- ^ Lester L. Grabbe calls the story of the sexual intercourse betwixt angels and women "an old myth in Judaism". Farther, he states: "the question of whether the myth is an interpretation of Genesis or whether Genesis represents a cursory reflection of the myth is debated."[xi]

- ^ "There is no unanimity among scholars when it comes to the sinlessness of angels. The bulk, of form, take the view that they are sinless. They first from the Quran and refer to private verses that speak for it, such equally (66: half dozen and (21:20). Hasan is counted amid every bit one of the beginning representatives of this doctrine, merely he obviously appears to be one step further than his contemporaries: he did not settle for the verses that speak for it, but tried to reinterpret the verses that speak against it differently." "In der Frage nach der Sündlosigkeit der Engel herrscht keine Einstimmigkeit unter den Gelehrten. Dice Mehrheit vertritt freilich, die Ansicht, dass sie sündlos sind. Sie geht vom Koran aus und beruft sich auf einzelne Verse, die dafür sprechen, wie zum Beispiel (66:6 und (21:xx). Zu ihnen wird Hasan als einer der ersten Vertreter dieser Lehre gezählt. Er scheint aber offentsichtlich noch einen Schritt weiter mit dieser Frage gekommen zu sein als seine Zeitgenossen. Er begnüngte sich nicht mit den Versen, dice dafür sprechen, sondern versuchte, auch dice Verse, die gerade dagegen sprechen, anders zu interpretieren."[89]

- ^ Still, a narrative attributed to Ibn Hazm states that the affections Sandalphon blamed the Jews for venerating Metatron every bit "son of God" "10 days each year".[100]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c "Mehdi Azaiez, Gabriel Said Reynolds, Tommaso Tesei, Hamza M. Zafer The Qur'an Seminar Commentary / Le Qur'an Seminar: A Collaborative Study of l Qur'anic Passages / Commentaire collaboratif de fifty passages coraniques Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG ISBN 978-3110445459 Q 72

- ^ Mahmoud Ayoub The Qur'an and Its Interpreters, Book 1 SUNY Press 1984 ISBN 978-0873957274 p. 74

- ^ Valerie Hoffman The Essentials of Ibadi Islam Syracuse University Printing 2012 ISBN 978-0815650843 p. 189

- ^ Al-Saïd Muhammad Badawi Arabic–English Dictionary of Qurʾanic Usage K. A. Abdel Haleem ISBN 978-9-004-14948-9, p. 864

- ^ Fr. Edmund Teuma The Nature of "Ibli$h in the Qur'an as Interpreted by the Commentators University of Malta pp. 15–16

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse Academy Press 2009 ISBN 978-0815650706 p. 39

- ^ Lester L. Grabbe, An Introduction to Offset Century Judaism: Jewish Organized religion and History in the Second Temple Period (Continuum International Publishing Group 1996 ISBN 978-0567085061), p. 101

- ^ ἐγρήγορος. Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek–English Lexicon revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940. p. 474. Available online at the Perseus Project Texts Loaded nether PhiloLogic (ARTFL project) at the Academy of Chicago.

- ^ Lester L. Grabbe, A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period (Continuum 2004 ISBN 978-0567043528), p. 344

- ^ Matthew Black, The Book of Enoch or I Enoch: A New English language Edition with Commentary and Textual Notes (Brill 1985 ISBN 978-9004071001), p. fourteen

- ^ Grabbe 2004, p. 101

- ^ Andrei A. Orlov, Night Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early on Jewish Demonology (SUNY Printing 2011 ISBN 978-i-43843951-8), p. 164

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. 256

- ^ a b Laurence, Richard (1883). "The Book of Enoch the Prophet".

- ^ Ra'anan Due south. Boustan, Annette Yoshiko Reed Heavenly Realms and Earthly Realities in Late Antique Religions Cambridge University Press 2004 ISBN 978-1-139-45398-1 p. 60

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. half dozen

- ^ SUTER, DAVID. Fallen Affections, Fallen Priest: The Trouble of Family Purity in ane Enoch 6—16. Hebrew Spousal relationship Higher Annual, vol. 50, 1979, pp. 115–135. JSTOR,

- ^ George Westward. E. Nickelsburg. "Apocalyptic and Myth in 1 Enoch six–xi." Periodical of Biblical Literature, vol. 96, no. iii, 1977, pp. 383–405

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-1139446877 pp. 103–104

- ^ a b Andrei Orlov, Gabriele Boccaccini New Perspectives on 2 Enoch: No Longer Slavonic Only Brill 2012 ISBN 978-9004230149 pp. 150, 164

- ^ Orlov 2011, p. 164

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 64: "In ii Enoch eighteen:3... the fall of Satan and his angels is talked of in terms of the Watchers (Grigori) story, and connected with Genesis six:1–4."

- ^ Howard Schwartz Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 978-0195327137 p. 108

- ^ "The Book of Enoch the Prophet: Chapter I-XX". www.sacred-texts.com.

- ^ Todd R. Hanneken The Subversion of the Apocalypses in the Volume of Jubilees Club of Biblical Lit ISBN 978-1589836433 p. 57

- ^ Todd R. Hanneken The Subversion of the Apocalypses in the Book of Jubilees Society of Biblical Lit ISBN 978-1589836433 p. 59

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge Academy Press 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. 90

- ^ a b c Chad T. Pierce Spirits and the Proclamation of Christ: i Peter 3:eighteen–22 in Calorie-free of Sin and Punishment Traditions in Early Jewish and Christian Literature Mohr Siebeck 2011 ISBN 978-3161508585 p. 112

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity Cornell Academy Press 1987 ISBN 978-0801494093 p. 193

- ^ Todd R. Hanneken The Subversion of the Apocalypses in the Book of Jubilees Lodge of Biblical Lit ISBN 978-1589836433 p. sixty

- ^ https://www.hs.ias.edu/files/Crone_Book_of_Watchers.pdf Archived 2019-09-23 at the Wayback Car: Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. half dozen (from The Qurʾānic Pagans and Related Matters: Nerveless Studies in Three Volumes, Band 1)

- ^ Geoffrey W. Dennis The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition Llewellyn Worldwide 2016 ISBN 978-0-738-74814-6

- ^ Yuri Stoyanov The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy Yale University Press 2000 ISBN 978-0-300-19014-4

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed, Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Printing 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. 266

- ^ a b Rachel Adelman The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha Brill 2009 ISBN 978-9004180611 pp. 77–80

- ^ Adele Berlin; Maxine Grossman, eds. (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-xix-973004-ix. Retrieved 2012-07-03

- ^ Christian D Ginsburg The Kabbalah (Routledge Revivals): Its Doctrines, Development, and Literature Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1317588887 p. 109

- ^ a b Michael Laitman, The Zohar

- ^ Aryeh Wineman, Mystic Tales from the Zohar Princeton University Press ISBN 978-0691058337 p. 48

- ^ a b c d Martin, Dale Basil. When Did Angels Become Demons? Periodical of Biblical Literature, vol. 129, no. 4, 2010, pp. 657–677. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25765960.

- ^ J. Daryl Charles The Angels under Reserve in two Peter and Jude Bulletin for Biblical Research Vol. 15, No. 1 (2005), pp. 39–48

- ^ Revelation 12:4

- ^ Revelation 12:ix

- ^ Packer, J.I. (2001). "Satan: Fallen angels accept a leader". Concise theology : a guide to celebrated Christian beliefs. Carol Stream, Ill.: Tyndale House. ISBN978-0842339605.

- ^ John Due north. Oswalt (1986). "The Book of Isaiah, Capacity 1–39". The International Commentary on the Onetime Attestation. Eerdmans. p. 320. ISBN978-0-8028-2529-ii . Retrieved 2012-07-03 .

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler Heaven and Hell in Comparative Faith: With Special Reference to Dante's Divine One-act Macmillan original: Princeton Academy 1923 digitized: 2008 p. 5

- ^ Hector Chiliad. Patmore, Adam, Satan, and the King of Tyre (Brill 2012), ISBN 978-9-00420722-6, pp. 76–78

- ^ Paul Peterson, Ross Cole (editors), Hermeneutics, Intertextuality and the Contemporary Meaning of Scripture (Avondale Academic Press 2013 ISBN 978-1-92181799-1), p. 246.

- ^ Gregory A. Boyd, God at State of war: The Bible & Spiritual Conflict, InterVarsity Press 1997 ISBN 978-0830818853, p. 138

- ^ a b Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. iv

- ^ a b Reed 2005, pp. 14, 15

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. 149

- ^ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. thirty

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. 163

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge Academy Press 2005 ISBN 978-0521853781 p. 162

- ^ Tim Hegedus Early Christianity and Ancient Astrology Peter Lang 2007 ISBN 978-0-820-47257-7 p. 127

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early Christian Tradition Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 978-0801494130 p. 130

- ^ Philip C. Almond The Devil: A New Biography I.B.Tauris 2014 ISBN 978-0857734884 p. 42

- ^ Charlesworth 2010, p. 149

- ^ Schwartz 2004, p. 108

- ^ "Match". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-03-11 .

- ^ Reed 2005, p. 218

- ^ Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. five

- ^ a b c David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-nine-004-35061-8 p. 39

- ^ Heinz Schreckenberg, Kurt Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity (Van Gorcum, 1992, ISBN 978-9023226536), p. 253

- ^ a b David 50 Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. 42

- ^ a b c d Joad Raymond Milton's Angels: The Early-Mod Imagination OUP Oxford 2010 ISBN 978-0199560509 p. 77

- ^ a b David Fifty Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. twoscore

- ^ David Fifty Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. 49

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early Christian Tradition Cornell University Printing 1987 ISBN 978-0801494130 p. 210

- ^ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-eight p. 45

- ^ a b Christoph Horn Augustinus, De civitate dei Oldenbourg Verlag 2010 ISBN 978-3050050409 p. 158

- ^ Neil Forsyth The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth Princeton Academy Press 1989 ISBN 978-0-691-01474-6 p. 405

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early on Christian Tradition Cornell Academy Press 1987 ISBN 978-0801494130 p. 211

- ^ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-eight p. 47

- ^ Joad Raymond Milton'due south Angels: The Early-Modern Imagination OUP Oxford 2010 ISBN 978-0199560509 p. 72

- ^ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 p. 44

- ^ "Catechism of the Cosmic Church, "The Fall of the Angels" (391–395)". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2012-07-03 .

- ^ Frank K. Flinn Encyclopedia of Catholicism Infobase Publishing 2007 ISBN 978-0-816-07565-2 p. 226

- ^ Charles Stewart Demons and the Devil: Moral Imagination in Modern Greek Culture Princeton University Press 2016 ISBN 978-1400884391 p. 141

- ^ Ernst Benz The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life Routledge 2017 ISBN 978-1351304740 p. 52

- ^ a b Sergiĭ Bulgakov The Orthodox Church St Vladimir's Seminary Printing 1988 ISBN 978-0881410518 p. 128

- ^ Charles Stewart Demons and the Devil: Moral Imagination in Modern Greek Culture Princeton University Press 2016 ISBN 978-1400884391 p. 147

- ^ Loren T. Stuckenbruck, Gabriele Boccaccini Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality SBL Press 2016 ISBN 978-0884141181 p. 133

- ^ James H. Charlesworth The Onetime Testament Pseudepigrapha Hendrickson Publishers 2010 ISBN 978-1598564914 p. 10

- ^ Peter Marshall, Alexandra Walsham Angels in the Early on Modern Globe Cambridge University Printing 2006 ISBN 978-0521843324 p. 74

- ^ Peter Marshall, Alexandra Walsham Angels in the Early on Mod World Cambridge University Press 2006 ISBN 978-0521843324 p. 76

- ^ Welch, Alford T. (2008) Studies in Qur'an and Tafsir. Riga, Latvia: Scholars Press. p. 756.

- ^ Omar Hamdan Studien zur Kanonisierung des Korantextes: al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrīs Beiträge zur Geschichte des Korans Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2006 ISBN 978-3447053495 pp. 291–292 (High german)

- ^ Masood Ali Khan, Shaikh Azhar Iqbal Encyclopaedia of Islam: Religious doctrine of Islam Commonwealth, 2005 ISBN 978-8131100523 p. 153

- ^ Austin P. Evans A commentary on the Creed of Islam Translated by Earl Edgar Elder Columbia Academy Press, New York 1980 isbn 8369-9259-8 p. 135

- ^ T.C. t.c Istanbul Bilimler Enstitütüsü Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Temel Islam bilimeri Anabilim dali yüksek Lisans Tezi Imam Maturidi'nin Te'vilatu'l-Kur'an'da gaybi Konulara Yaklasimi Elif Erdogan 2501171277 Danisman Prof. Dr. Yaşar Düzenli İstanbul 202

- ^ Amira El-Zein The Evolution of the Concept of the Jinn 1995 p. 232

- ^ Christoph Auffarth, Loren T. Stuckenbruck The Fall of the Angels Brill 2004 ISBN 978-9-004-12668-8 p. 161

- ^ Syria in Crusader Times: Conflict and Co-Beingness. (2020). Vereinigtes Königreich: Edinburgh University Printing.

- ^ Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3 p. 30

- ^ Muham Sakura Dragon The Corking Tale of Prophet Enoch (Idris) In Islam Sakura Dragon SPC ISBN 978-1519952370

- ^ Kohlberg, Due east. (2020). In Praise of the Few. Studies in Shiʿi Thought and History

- ^ Steven M. Wasserstrom Between Muslim and Jew: The Trouble of Symbiosis under Early Islam Princeton University Press 2014 ISBN ISBN 978-1400864133 p. 183

- ^ Hava Lazarus-Yafeh Intertwined Worlds: Medieval Islam and Bible Criticism Princeton University Press 2004 ISBN 978-i-4008-6273-3 p. 32

- ^ Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. 16

- ^ Q2:30, 50+ translations, islamawakened.com]

- ^ a b c Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Disharmonize, Revision and Reception Brill 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 p. 66

- ^ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception Brill 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 p. seventy

- ^ Jacques Waardenburg Islam: Historical, Social, and Political Perspectives Walter de Gruyter, 2008 ISBN 978-3-110-20094-2 p. 38

- ^ Mustafa Öztürk The Tragic Story of Iblis (Satan) in the Qur'an Journal of Islamic Inquiry, p. 136

- ^ Al-Tabari J. Cooper W.F. Madelung and A. Jones The commentary on the Quran past Abu Jafar Muhammad B. Jarir al-Tabari being an abbridged translation of Jamil' al-bayan 'an ta'wil ay al-Qur'an Oxford Academy Press Hakim Investment Holdings p. 239

- ^ Mahmoud M. Ayoub Qur'an and Its Interpreters, The, Volume 1, Band 1 SUNY Press ISBN 978-0791495469 p. 75

- ^ a b Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Disharmonize, Revision and Reception Brill 2016 ISBN 978-nine-004-33481-6 p. 71

- ^ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception Brill 2016 ISBN 978-ix-004-33481-6 p. 72

- ^ Paul van Geest, Marcel Poorthuis, Els Rose Sanctifying Texts, Transforming Rituals: Encounters in Liturgical Studies Brill 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-34708-3 p. 83

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent Globe of the Jinn Syracuse University Printing 2009 ISBN 978-0815650706 p. 45

- ^ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1136504747 p. viii

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent Globe of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0815650706 p. twoscore

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said, "Angels", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 16 October 2019 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23204> Erste Online-Erscheinung: 2009 Erste Druckedition: ISBN 978-9004181304, 2009, 2009-3

- ^ Hussein Abdul-Raof Theological Approaches to Qur'anic Exegesis: A Applied Comparative-Contrastive Analysis Routledge 2012 ISBN 978-1-136-45991-vii p. 155

- ^ Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. ten

- ^ Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, pp. 10–11

- ^ Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurān, p. eleven

- ^ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the Afterlives of Enochic Traditions in Early Islam Academy of Pennsylvania 2015 p. half dozen

- ^ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception Brill 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-half-dozen p. 78

- ^ Wallace Fowlie A Reading of Dante's Inferno University of Chicago Printing ISBN 978-0-226-25888-i p. seventy

- ^ Andrew Milner Literature, Culture and Society Routledge 2017 ISBN 978-1-134-94950-2 chapter 5

- ^ a b Biljana Ježik The Fallen Angels in Milton'southward Paradise Lost Osijek, 2014 p. 4

- ^ Biljana Ježik The Fallen Angels in Milton's Paradise Lost Osijek, 2014 p. 2

- ^ Benjamin Myers Milton's Theology of Freedom Walter de Gruyter 2012 ISBN 978-3110919370 pp. 54, 59

- ^ Benjamin Myers Milton's Theology of Freedom Walter de Gruyter 2012 ISBN 978-3110919370 p. 60

- ^ Henry F. Majewski Paradigm & Parody: Images of Creativity in French Romanticism--Vigny, Hugo, Balzac, Gautier, Musset University of Virginia Press 1989 ISBN 978-0813911779 p. 157

- ^ Bamberger, Bernard J. (2006). Fallen angels : soldiers of Satan's realm (kickoff paperback ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Jewish Publ. Soc. of America. ISBN 978-0-8276-0797-2 p. iv

References [edit]

- Anderson, Gary, ed. (2000). Literature on Adam and Eve. Leiden: Brill. ISBN978-9004116009.

- Bamberger, Bernard J. (2006). Fallen angels : soldiers of Satan's realm (first paperback ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Jewish Publ. Soc. of America. ISBN978-0-8276-0797-2.

- Charlesworth, James H., ed. (2010). The Old Testament pseudepigrapha. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson. ISBN978-1598564914.

- Davidson, Gustav (1994). A lexicon of angels: including the fallen angels (1st Free Press pbk. ed.). New York: Free Press. p. 111. ISBN978-0-02-907052-9.

- DDD, Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter W. van der Horst (1998). Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible (DDD) (ii., extensively rev. ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN978-9004111196.

- Douglas, James D.; Merrill, Chapin Tenney; Silva, Moisés, eds. (2011). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. ISBN978-0-310-22983-4.

- Orlov, Andrei A. (2011). Dark mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in early Jewish demonology. Albany: Country University of New York Printing. ISBN978-one-4384-3951-viii.

- Reed, Annette Yoshiko (2005). Fallen angels and the history of Judaism and Christianity : the reception of Enochic literature (ane. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Academy Press. p. 1. ISBN978-0521853781.

- Schwartz, Howard (2004). Tree of souls: The mythology of Judaism. New York: Oxford U Pr. ISBN978-0195086799.

- Wright, Archie T. (2004). The origin of evil spirits the reception of Genesis 6.1–4 in early Jewish literature. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN978-3-16-148656-2.

Further reading [edit]

- Ashley, Leonard R.Due north. (September 2011). The complete volume of devils and demons. New York: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN978-1616083335.

External links [edit]

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Angels, encounter section "The Evil Angels"

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Fall of Angels

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fallen_angel

0 Response to "Again the Devil Deceived a Third of the Angels of Heaven"

Post a Comment