Encyclopedia or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences Arts and Crafts

The title page of the Encyclopédie | |

| Author | Numerous contributors, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Linguistic communication | French |

| Subject | General |

| Genre | Reference encyclopedia |

| Publisher | André le Breton, Michel-Antoine David, Laurent Durand and Antoine-Claude Briasson |

| Publication engagement | 1751–1766 |

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (English: Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Lexicon of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts),[1] better known as Encyclopédie , was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis Diderot and, until 1759, co-edited by Jean le Rond d'Alembert.[2]

The Encyclopédie is nearly famous for representing the idea of the Enlightenment. According to Denis Diderot in the article "Encyclopédie", the Encyclopédie's aim was "to change the way people remember" and for people (bourgeoisie) to be able to inform themselves and to know things.[3] He and the other contributors advocated for the secularization of learning away from the Jesuits.[four] Diderot wanted to incorporate all of the world'south knowledge into the Encyclopédie and hoped that the text could disseminate all this information to the public and future generations.[5]

It was also the outset encyclopedia to include contributions from many named contributors, and information technology was the beginning full general encyclopedia to describe the mechanical arts. In the first publication, seventeen folio volumes were accompanied by detailed engravings. Later volumes were published without the engravings, in guild to better reach a wide audience within Europe.[6]

Origins [edit]

The Encyclopédie was originally conceived as a French translation of Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia (1728).[seven] Ephraim Chambers had first published his Cyclopaedia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences in 2 volumes in London in 1728, following several dictionaries of arts and sciences that had emerged in Europe since the tardily 17th century.[eight] [9] This piece of work became quite renowned, and iv editions were published between 1738 and 1742. An Italian translation appeared between 1747 and 1754. In French republic a member of the banking family Lambert had started translating Chambers into French,[ten] only in 1745 the expatriate Englishman John Mills and German language Gottfried Sellius were the first to really prepare a French edition of Ephraim Chambers'south Cyclopaedia for publication, which they entitled Encyclopédie.

Early in 1745 a prospectus for the Encyclopédie [xi] was published to attract subscribers to the project. This four page prospectus was illustrated by Jean-Michel Papillon,[12] and accompanied past a plan, stating that the work would exist published in five volumes from June 1746 until the end of 1748.[xiii] The text was translated by Mills and Sellius, and it was corrected past an unnamed person, who appears to have been Denis Diderot.[14]

The prospectus was reviewed quite positively and cited at some length in several journals.[15] The Mémoires cascade l'histoire des sciences et des beaux arts journal was lavish in its praise: "voici deux des plus fortes entreprises de Littérature qu'on ait faites depuis long-temps" (here are two of the greatest efforts undertaken in literature in a very long time).[16] The Mercure Journal in June 1745, printed a 25-page commodity that specifically praised Mills' function every bit translator; the Journal introduced Mills every bit an English scholar who had been raised in French republic and who spoke both French and English as a native. The Journal reported that Mills had discussed the work with several academics, was zealous most the project, had devoted his fortune to support this enterprise, and was the sole owner of the publishing privilege.[17]

Nevertheless, the cooperation fell apart later on in 1745. André le Breton, the publisher deputed to manage the physical production and sales of the volumes, cheated Mills out of the subscription money, claiming for example that Mills'southward knowledge of French was inadequate. In a confrontation Le Breton physically assaulted Mills. Mills took Le Breton to court, but the court decided in Le Breton's favour. Mills returned to England shortly after the court's ruling.[18] [19] For his new editor, Le Breton settled on the mathematician Jean Paul de Gua de Malves. Amidst those hired by Malves were the young Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Denis Diderot. Inside 13 months, in August 1747, Gua de Malves was fired for being an ineffective leader. Le Breton then hired Diderot and d'Alembert to be the new editors.[20] Diderot would remain as editor for the adjacent twenty-five years, seeing the Encyclopédie through to its completion; d'Alembert would go out this role in 1758. Every bit d'Alembert worked on the Encyclopédie, its championship expanded. As of 1750, the full title was Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une société de gens de lettres, mis en ordre par M. Diderot de l'Académie des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Prusse, et quant à la partie mathématique, par Grand. d'Alembert de l'Académie royale des Sciences de Paris, de celle de Prusse et de la Société royale de Londres. ("Encyclopedia: or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, by a Company of Persons of Letters, edited by M. Diderot of the Academy of Sciences and Belles-lettres of Prussia: as to the Mathematical Portion, arranged by G. d'Alembert of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Paris, of the Academy of Sciences in Prussia and of the Royal Order of London.") The title folio was amended as d'Alembert acquired more titles.

Publication [edit]

Excerpt from the frontispiece of the Encyclopédie (1772). It was drawn past Charles-Nicolas Cochin and engraved by Bonaventure-Louis Prévost. The work is laden with symbolism: The figure in the centre represents truth—surrounded past bright light (the central symbol of the Enlightenment). Two other figures on the right, reason and philosophy, are tearing the veil from truth.

The work consisted of 28 volumes, with 71,818 articles and three,129 illustrations.[21] The first seventeen volumes were published betwixt 1751 and 1765; eleven volumes of plates were finished by 1772. Engraver Robert Bénard provided at least 1,800 plates for the work. The Encyclopédie sold 4,000 copies during its first xx years of publication and earned a profit of 2 million livres for its investors.[22] Considering of its occasional radical contents (see "Contents" below), the Encyclopédie caused much controversy in conservative circles, and on the initiative of the Parlement of Paris, the French government suspended the encyclopedia's privilège in 1759.[23] Interestingly enough, the Encyclopédie had also been banned 1752 subsequently publication of the second volume.[24] Despite these issues, work continued "in secret," partially considering the project had highly placed supporters, such every bit Malesherbes and Madame de Pompadour.[25] The authorities deliberately ignored the continued work; they thought their official ban was sufficient to appease the church building and other enemies of the project.

During the "secretive" flow, Diderot accomplished a well-known work of subterfuge. The title pages of volumes ane through 7, published between 1751 and 1757, claimed Paris as the place of publication. However, the championship pages of the subsequent text volumes, 8 through 17, published together in 1765, show Neufchastel every bit the place of publication. Neuchâtel is safely across the French edge in what is now role of Switzerland but which was so an independent principality,[26] where official production of the Encyclopédie was secure from interference past agents of the French country. In particular, regime opponents of the Encyclopédie could not seize the production plates for the Encyclopédie in Paris because those printing plates ostensibly existed only in Switzerland. Meanwhile, the actual product of volumes 8 through 17 quietly continued in Paris.

In 1775, Charles Joseph Panckoucke obtained the rights to reissue the work. He issued 5 volumes of supplementary material and a two-book index from 1776 to 1780. Some scholars include these seven "extra" volumes as function of the first total issue of the Encyclopédie, for a total of 35 volumes, although they were not written or edited by the original authors.

From 1782 to 1832, Panckoucke and his successors published an expanded edition of the work in some 166 volumes as the Encyclopédie Méthodique. That work, enormous for its time, occupied a thousand workers in production and 2,250 contributors.

Contributors [edit]

Since the objective of the editors of the Encyclopédie was to gather all the knowledge in the world, Diderot and D'Alembert knew they would need various contributors to assist them with their project.[27] Many of the philosophes (intellectuals of the French Enlightenment) contributed to the Encyclopédie, including Diderot himself, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu.[7] The most prolific correspondent was Louis de Jaucourt, who wrote 17,266 articles between 1759 and 1765, or most eight per twenty-four hours, representing a full 25% of the Encyclopédie. The publication became a place where these contributors could share their ideas and interests.

However, as Frank Kafker has argued, the Encyclopedists were not a unified group:[28]

... despite their reputation, [the Encyclopedists] were not a close-knit group of radicals intent on subverting the One-time Regime in France. Instead they were a disparate group of men of messages, physicians, scientists, craftsmen and scholars ... fifty-fifty the small minority who were persecuted for writing manufactures belittling what they viewed every bit unreasonable customs—thus weakening the might of the Catholic Church and undermining that of the monarchy—did non envision that their ideas would encourage a revolution.

Following is a listing of notable contributors with their area of contribution (for a more detailed list, meet Encyclopédistes):

- Jean Le Rond d'Alembert – editor; scientific discipline (peculiarly mathematics), contemporary diplomacy, philosophy, organized religion, amid others

- Claude Bourgelat – manège, farriery

- André le Breton – chief publisher; article on printer'south ink

- Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton – natural history

- Denis Diderot – principal editor; economics, mechanical arts, philosophy, politics, religion, amongst others

- Businesswoman d'Holbach – scientific discipline (chemistry, mineralogy), politics, faith, among others

- Chevalier Louis de Jaucourt – economics, literature, medicine, politics, bookbinding, among others

- Jean-Baptiste de La Chapelle – mathematics

- Abbé André Morellet – theology, philosophy

- Montesquieu – part of the article "Goût" ("Taste")

- François Quesnay – manufactures on tax farmers and grain

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau – music, political theory

- Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune – economics, etymology, philosophy, physics

- Voltaire – history, literature, philosophy

Due to the controversial nature of some of the articles, several of its editors were sent to jail.[29]

Contents and controversies [edit]

Structure [edit]

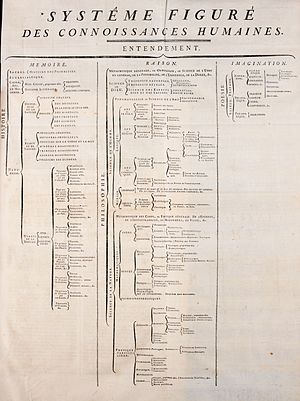

Like well-nigh encyclopedias, the Encyclopédie attempted to collect and summarize human noesis in a variety of fields and topics, ranging from philosophy to theology to scientific discipline and the arts. The Encyclopédie was controversial for reorganizing knowledge based on human reason instead of by nature or theology.[30] Knowledge and intellect branched from the three categories of human thought, whereas all other perceived aspects of knowledge, including theology, were but branches or components of these human-made categories.[31] The introduction to the Encyclopédie, D'Alembert's "Preliminary Discourse", is considered an important exposition of Enlightenment ideals.

Religious and political controversies [edit]

They harshly criticized superstition as an intellectual error in his article on the topic.[32] They therefore doubted the authenticity of presupposed historical events cited in the Bible and questioned the validity of miracles and the Resurrection.[33] However, some gimmicky scholars argue the skeptical view of miracles in the Encyclopédie may exist interpreted in terms of "Protestant debates about the cessation of the charismata."[34]

These challenges led to suppression from church building and state authorities. The Encyclopédie and its contributors endured many attacks and attempts at censorship past the clergy or other censors, which threatened the publication of the projection every bit well as the authors themselves. The King'south Council suppressed the Encyclopédie in 1759.[35] The Catholic Church, under Pope Clement XIII, placed it on its list of banned books. Prominent intellectuals criticized it, about famously Lefranc de Pompignan at the French University. A playwright, Charles Palissot de Montenoy, wrote a play chosen Les Philosophes to criticize the Encyclopédie.[36] When Abbé André Morellet, ane of the contributors to the Encyclopédie, wrote a mock preface for it, he was sent to the Bastille due to allegations of libel.[37]

To defend themselves from controversy, the encyclopedia's manufactures wrote of theological topics in a mixed fashion. Some articles supported orthodoxy, and some included overt criticisms of Christianity. To avoid straight retribution from censors, writers frequently hid criticism in obscure manufactures or expressed information technology in ironic terms.[38] Nonetheless, the contributors withal openly attacked the Catholic Church in certain articles with examples including criticizing excess festivals, monasteries, and celibacy of the clergy.[39]

Politics and society [edit]

The Encyclopédie is often seen as an influence for the French Revolution because of its emphasis on Enlightenment political theories. Diderot and other authors, in famous manufactures such as "Political Dominance", emphasized the shift of the origin of political say-so from divinity or heritage to the people. This Enlightenment platonic, consort by Rousseau and others, advocated that people accept the right to consent to their government in a course of social contract.[forty]

Some other major, contentious component of political issues in the Encyclopédie was personal or natural rights. Articles such as "Natural Rights" by Diderot explained the human relationship between individuals and the general will. The natural land of humanity, according to the authors, is barbaric and unorganized. To rest the desires of individuals and the needs of the full general volition, humanity requires civil society and laws that benefit all persons. Writers, to varying degrees, criticized Thomas Hobbes' notions of a selfish humanity that requires a sovereign to dominion over it.[41]

In terms of economic science, the Encyclopédie expressed favor for laissez-faire ideals or principles of economic liberalism. Articles apropos economics or markets, such as "Economic Politics", generally favored free competition and denounced monopolies. Manufactures often criticized guilds every bit creating monopolies and approved of state intervention to remove such monopolies. The writers advocated extending laissez-faire principles of liberalism from the market to the individual level, such as with privatization of teaching and opening of careers to all levels of wealth.[42]

Science and technology [edit]

At the same time, the Encyclopédie was a vast compendium of noesis, notably on the technologies of the menses, describing the traditional arts and crafts tools and processes. Much information was taken from the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers. These manufactures applied a scientific approach to agreement the mechanical and production processes, and offered new ways to improve machines to make them more efficient.[43] Diderot felt that people should take access to "useful knowledge" that they can apply to their everyday life.[44]

Influence [edit]

The Encyclopédie played an important role in the intellectual foment leading to the French Revolution. "No encyclopaedia perhaps has been of such political importance, or has occupied so conspicuous a place in the civil and literary history of its century. It sought not but to give data, but to guide stance," wrote the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. In The Encyclopédie and the Age of Revolution, a work published in conjunction with a 1989 exhibition of the Encyclopédie at the University of California, Los Angeles, Clorinda Donato writes the following:

The encyclopedians successfully argued and marketed their belief in the potential of reason and unified knowledge to empower human will and thus helped to shape the social bug that the French Revolution would address. Although it is hundred-to-one whether the many artisans, technicians, or laborers whose work and presence are interspersed throughout the Encyclopédie actually read it, the recognition of their work equally equal to that of intellectuals, clerics, and rulers prepared the terrain for demands for increased representation. Thus the Encyclopédie served to recognize and galvanize a new ability base, ultimately contributing to the devastation of former values and the creation of new ones (12).

While many contributors to the Encyclopédie had no interest in radically reforming French order, the Encyclopédie as a whole pointed that way. The Encyclopédie denied that the teachings of the Catholic Church building could be treated every bit authoritative in matters of science. The editors also refused to care for the decisions of political powers every bit definitive in intellectual or artistic questions. Some manufactures talked virtually changing social and political institutions that would improve their society for anybody.[45] Given that Paris was the intellectual uppercase of Europe at the time and that many European leaders used French as their authoritative language, these ideas had the chapters to spread.[23]

The Encyclopédie 's influence continues today.[46] Historian Dan O'Sullivan compares information technology to Wikipedia:

Similar Wikipedia, the Encyclopédie was a collaborative effort involving numerous writers and technicians. As do Wikipedians today, Diderot and his colleagues needed to engage with the latest technology in dealing with the problems of designing an upwards-to-date encyclopedia. These included what kind of information to include, how to gear up upward links between diverse articles, and how to attain the maximum readership.[47]

Statistics [edit]

Approximate size of the Encyclopédie:

- 17 volumes of articles, issued from 1751 to 1765

- 11 volumes of illustrations, issued from 1762 to 1772

- 18,000 pages of text

- 75,000 entries

- 44,000 main articles

- 28,000 secondary articles

- 2,500 analogy indices

- 20,000,000 words in total

Print run: 4,250 copies (annotation: fifty-fifty single-volume works in the 18th century seldom had a print run of more than one,500 copies).[48]

Quotations [edit]

- "The goal of an encyclopedia is to gather all the knowledge scattered on the surface of the earth, to demonstrate the full general system to the people with whom we live, & to transmit it to the people who will come up afterwards the states, and so that the works of centuries past is not useless to the centuries which follow, that our descendants, by becoming more learned, may go more virtuous & happier, & that nosotros do non die without having merited being function of the human race." (Encyclopédie, Diderot)[49] [50]

- "Reason is to the philosopher what grace is to the Christian... Other men walk in darkness; the philosopher, who has the same passions, acts only subsequently reflection; he walks through the dark, but it is preceded by a torch. The philosopher forms his principles on an infinity of detail observations. He does not confuse truth with plausibility; he takes for truth what is true, for forgery what is false, for doubtful what is hundred-to-one, and probable what is likely. The philosophical spirit is thus a spirit of observation and accuracy." (Philosophers, Dumarsais)

- "If exclusive privileges were not granted, and if the financial organization would non tend to concentrate wealth, there would be few great fortunes and no quick wealth. When the means of growing rich is divided between a greater number of citizens, wealth will likewise be more than evenly distributed; extreme poverty and extreme wealth would be likewise rare." (Wealth, Diderot)

- "Aguaxima, a constitute growing in Brazil and on the islands of Southward America. This is all that we are told about it; and I would like to know for whom such descriptions are made. It cannot be for the natives of the countries concerned, who are likely to know more about the aguaxima than is independent in this description, and who practice not demand to learn that the aguaxima grows in their country. It is equally if you said to a Frenchman that the pear tree is a tree that grows in France, in Germany, etc. Information technology is not meant for usa either, for what do we care that in that location is a tree in Brazil named aguaxima, if all we know about it is its name? What is the signal of giving the proper name? It leaves the ignorant merely as they were and teaches the rest of us nothing. If all the same I mention this plant here, forth with several others that are described just every bit poorly, and so information technology is out of consideration for certain readers who prefer to find cipher in a dictionary article or even to find something stupid than to find no article at all." (Aguaxima, Diderot)

Facsimiles [edit]

Readex Microprint Corporation, NY 1969. 5 vol. The total text and images reduced to iv double-spread pages of the original actualization on i folio-sized page of this press.

Subsequently released past the Pergamon Printing, NY and Paris with ISBN 0-08-090105-0.

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Ian Buchanan, A Dictionary of Critical Theory, Oxford Academy Press, 2010, p. 151.

- ^ "Encyclopédie | French reference work". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ Denis Diderot every bit quoted in Hunt, p. 611

- ^ University of the State of New York (1893). Annual Report of the Regents, Volume 106. p. 266.

- ^ Denis Diderot as quoted in Kramnick, p. 17.

- ^ Lyons, M. (2013). Books: a living history. London: Thames & Hudson.

- ^ a b Magee, p. 124

- ^ Lough (1971. pp. 3–five)

- ^ Robert Shackleton "The Encyclopedie" in: Proceedings, American Philosophical Society (vol. 114, No. 5, 1970. p. 39)

- ^ Précis de la vie du citoyen Lambert, Bibliothèque nationale, Ln. 11217; Listed in Shackleton (1970, p. 130).

- ^ Recently rediscovered in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, run into Prospectus pour une traduction française de la Cyclopaedia de Chambers web log.bnf.fr, Dec. 2010

- ^ André-François Le Breton, Jean-Michel Papillon, Ephraim Chambers. Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire universel des arts et des sciences. 1745

- ^ Reproduction from 1745 original in: Luneau de Boisjermain (1771) Mémoire pour les libraires associés à l'Encyclopédie: contre le sieur Luneau de Boisjermain. p. 165.

- ^ Philipp Blom. Encyclopédie: the triumph of reason in an unreasonable age Fourth Estate, 2004. p. 37

- ^ "Prospectus du Dictionnaire de Chambers, traduit en François, et proposé par souscription" in: Grand. Desfontaines. Jugemens sur quelques ouvrages nouveaux. Vol 8. (1745). p. 72

- ^ Review in: Mémoires pour fifty'histoire des sciences et des beaux arts, May 1745, Nr. two. pp. 934–38

- ^ Mercure Periodical (1745, p. 87) cited in: Lough (1971), p. 20.

- ^ Mills' summary of this matter was published in Boisjermain's Mémoire pour P. J. F. Luneau de Boisjermain av. d. Piéc. justif 1771, pp. 162–63, where Boisjermain also gave his version of the events (pp. two–v).

- ^ Comments by Le Breton are published in his biography; in the preface of the encyclopedia; in John Lough (1971); etc.

- ^ Blom, pp. 39–40

- ^ "Entrepreneurs, Economic Growth, and the Enlightenment". Harvard Business Review. August 10, 2015. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved July 13, 2021 – via hbr.org.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books a Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 108. ISBN978-1-60606-083-4.

- ^ a b Magee, p. 125

- ^ Lyons, M. (2011). Books: A Living History (p. 34). Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- ^ Andrew S. Curran, Diderot and the Art of Thinking Freely, Other Press, 2019, p. 136-vii

- ^ Matheson, D (1992) Postcompulsory Education in Suisse romande, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glasgow

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 56.

- ^ "Fellow Projection Details". The Camargo Foundation. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Brown, Ian (July 8, 2017). "An Encyclopedia Brown story: Bound and determined to fight for the facts in the time of Trump". The Globe and Mail . Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ Darnton, pp. 7, 539

- ^ Brewer 1993, pp. xviii–23

- ^ Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Nativity of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing. pp. 51–two. ISBN978-0-226-40336-half dozen.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living story. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 106. ISBN978-i-60606-083-4.

- ^ Josephson-Tempest (2017), p. 55

- ^ "Diderot'due south Encyclopedia". Historical Text Annal.

- ^ Andrew Southward. Curran, Diderot and the Art of Thinking Freely, Other Printing, 2019, p. 183-6

- ^ Aldridge, Alfred Owen (2015). Voltaire and the Century of Calorie-free. Princeton Legacy Library. p. 266. ISBN9781400866953.

- ^ Lough, p. 236

- ^ Lough, pp. 258–66

- ^ Roche, p. 190

- ^ Roche, pp. 191–92

- ^ Lough, pp. 331–35

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 55

- ^ Shush, p. 17

- ^ Spielvogel, pp. 480–81

- ^ Miloš, Todorović (2018). "From Diderot's Encyclopedia to Wales's Wikipedia: a cursory history of collecting and sharing knowledge". Časopis KSIO. 1 (2018.): 88–102. doi:x.5281/zenodo.3235309. Retrieved September three, 2020.

- ^ O'Sullivan, p. 45

- ^ "Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, edited by Denis Diderot (1751-1780)". ZSR Library. November vii, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Blom, p. 139

- ^ "En effet, le but d'une Encyclopédie est de rassembler les connoissances éparses sur la surface de la terre; d'en exposer le système général aux hommes avec qui nous vivons, & de le transmettre aux hommes qui viendront après nous; afin que les travaux des siecles passés n'aient pas été des travaux inutiles pour les siecles qui succéderont; que nos neveux, devenant plus instruits, deviennent en même tems plus vertueux & plus heureux, & que nous ne mourions pas sans avoir bien mérité du genre humain." From uchicago.edu.

Bibliography [edit]

- Blom, Philipp, Enlightening the earth: Encyclopédie, the book that changed the course of history, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, ISBN one-4039-6895-0

- Brewer, Daniel (1993). The Soapbox of Enlightenment in Eighteenth-century France: Diderot and the Art of Philosophizing. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Up. ISBN978-0521414838.

- Brewer, Daniel, "The Encyclopédie: Innovation and Legacy" in New Essays on Diderot, edited by James Fowler, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 0-521-76956-half-dozen

- Burke, Peter, A social history of knowledge: from Gutenberg to Diderot, Malden: Blackwell Publishers Inc., 2000, ISBN 0-7456-2485-5

- Darnton, Robert. The Business organization of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie, 1775-1800. Cambridge: Belknap, 1979.

- Hunt, Lynn, The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures: A Concise History: Volume II: Since 1340, 2d Edition, Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2007, ISBN 0-312-43937-7

- Kramnick, Isaac, "Encyclopédie" in The Portable Enlightenment Reader, edited by Isaac Kramnick, Toronto: Penguin Books, 1995, ISBN 0-xiv-024566-9

- Lough, John. The Encyclopédie. New York: D. McKay, 1971.

- Magee, Bryan, The Story of Philosophy, New York: DK Publishing, Inc., 1998, ISBN 0-7894-3511-Ten

- O'Sullivan, Dan. Wikipedia: A New Customs of Practice? Farnham, Surrey, 2009, ISBN 9780754674337.

- Roche, Daniel. "Encyclopedias and the Diffusion of Knowledge." The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-century Political Thought. By Mark Goldie and Robert Wokler. Cambridge: Cambridge Upward, 2006. 172–94.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J, Western Civilization, Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2011, ISBN 0-495-89733-7

Further reading [edit]

- d'Alembert, Jean Le Rond. Preliminary discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot, translated past Richard N. Schwab, 1995. ISBN 0-226-13476-8

- Darnton, Robert. "The Encyclopédie wars of prerevolutionary France." American Historical Review 78.v (1973): 1331–1352. online

- Donato, Clorinda, and Robert M. Maniquis, eds. The Encyclopédie and the Historic period of Revolution. Boston: Thousand. Thou. Hall, 1992. ISBN 0-8161-0527-viii

- Encyclopédie ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Editions Flammarion, 1993. ISBN 2-08-070426-5

- Grimsley. Ronald. Jean d'Alembert (1963)

- Hazard, Paul. European thought in the eighteenth century from Montesquieu to Lessing (1954). pp. 199–224

- Kafker, Frank A. and Serena Fifty. Kafker. The Encyclopedists as individuals: a biographical dictionary of the authors of the Encyclopédie (1988) ISBN 0-7294-0368-8

- Lough, John. Essays on the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert Oxford Upwardly, 1968.

- Pannabecker, John R. Diderot, the Mechanical Arts, and the Encyclopédie, 1994. With bibliography.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers at Wikimedia Commons -

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: - "Encyclopédie". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Encyclopédie". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

-

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers - Digitized version of the Encyclopédie

- Diderot – search engine in tribute to Diderot

- University of Chicago on-line version with an English interface and the dates of publication

- Guide to the Engraving "Aiguiller-Bonnetier" from Diderot'south Encyclopedia 1762

- Encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project currently contains a growing drove of manufactures translated into English (3,053 manufactures and sets of plates as of September 30, 2020).

- Online Books Page presentation of the first edition

- The Encyclopédie, BBC Radio 4 word with Judith Hawley, Caroline Warman and David Wootton (In Our Time, Oct. 26, 2006)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclop%C3%A9die#:~:text=1751%E2%80%931766-,Encyclop%C3%A9die%2C%20ou%20dictionnaire%20raisonn%C3%A9%20des%20sciences%2C%20des%20arts%20et%20des,later%20supplements%2C%20revised%20editions%2C%20and

0 Response to "Encyclopedia or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences Arts and Crafts"

Post a Comment